Discovering Tilton, Part IV of IV

- Typewriter Gazette

- Sep 8, 2024

- 16 min read

What a Tangled Web They Wove

In Part III we uncovered the main mysteries that set off this body of research, and ended with a short history of the World index typewriter. Here in Part IV we find a web of stationery businesses and explore how the inter-relationships may have shaped their end-of-life activities. We also find out what life was like after the Tilton Mfg. Co., and hear about the end of the lives of Elliott G. Thorp and the Tilton brothers. This will be the final part of the Discovering Tilton series.

Thorp & Adams, Thorp & Martin, and Tilton

We bring our story back to the Tilton Mfg. Co., in February 1891, three years after incorporation. The company was reporting good sales of the Victor index, and stated that its Purchase St. factory was running full time (Boston, 1891). It was in the middle of this good fortune that the company announced it had plans to sell a new typewriter, the Franklin, the original patent of which was granted to Wellington P. Kidder of Boston, MA, on December 8, 1891 (Kidder, 1891). This had all been laid out in “Rethinking the Franklin”, but we had left open some questions regarding the relationship between Franklin Typewriter Co., and Tilton Mfg. Co. Through further research for the present article, we can now confirm that the Franklin Typewriter Co. and the Tilton Mfg. Co. were indeed separate, albeit interrelated, businesses. In our former article, we share that the Franklin Typewriter Co. went bankrupt. A thorough reading of the proceedings of the lawsuit to research the present article provided the following clue: “That the Franklin Typewriter Company is a corporation organized under the laws of the State of New York for the manufacture and sale of the typewriters known as the Franklin Typewriter and the Victor Typewriter, and is and at all the times hereinafter mentioned was engaged in the manufacture and sale of the said Franklin Typewriter and the Victor Typewriter.” (Gove v. Tower, 1907, pp. 160-161). The lawsuit, and another source, contains further information that Franklin Typewriter Co. was paying royalties to Tilton Mfg. Co. to be able to sell the machines at least between 1897 and 1902 (Jottings of the Trade, 1902; Gove v. Tower, 1907), so the two businesses must have been separate legal entities. It is also worth it to note that the New York office of the Tilton Mfg. Co. was listed as “dissolved” in 1892 (Smythe, 1911). The Franklin Typewriter Company had business in New York for much longer, moving its main operation there after the 1893 fire in the Purchase St. factory in Boston, meaning that there were periods in which the separate companies were not even co-located.

Over at Thorp & Adams, by April 1892, George E. Adams had retired from the company. Apparently not wanting to lose his stationery business, Dr. Thorp worked with T. Fred Martin to form Thorp & Martin Mfg. Co. (Obituary, 1895). This seems to be a point where Dr. Thorp gets into some financial difficulty of his own. In October 1893, the state of Massachusetts posted an announcement that several businesses had failed to file tax returns, and both “Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co.”, and “Thorp & Martin Co.”, were listed (State Wants Information, 1893). You may have noticed that the second company was missing the word “Manufacturing” from the name. Thorp & Martin Mfg. Co. had actually failed in September 1893, and the men formed the Thorp & Martin Co. at No. 12 Milk St. in Boston (Obituary, 1895; Sampson Murdock & Co., 1900). That address should ring a bell; it was the headquarters of Winkley, Dresser, & Co. back in 1884, and was also shared with the Cutter-Tower Co. at 12A Milk St.

So what happened to Thorp & Martin Mfg. Co.? On May 31, 1893, Thorp & Martin Mfg. Co. stipulated terms with their creditors to pay back their debt in dividends (Thorp & Co Win, 1894). It appears that initially the company had agreed to pay ⅓ of the debt in cash within 30 days so as to avoid defaulting on the debt as a whole. The debtors proposed instead that the company pay back the debt over a longer period of time, but ultimately for a larger amount (Business troubles, 1893). It seems this suggestion was agreed by most of the creditors, except for Hooper, Lewis, & Co. Instead the company sued directors Elliott G. Thorp, T. Fred Martin, and Charles S. Willard with individual liability on the grounds that they believed the debt of the corporation exceeded its capital stock (Thorp & Co Win, 1894). Luckily for the directors, the courts ruled in favor of the defendants on the grounds that the capital stock only fell below debt after the debt had been requested. Even so, it seems that this win did not stop the company from failing, which led to reorganization and the resulting Thorp & Martin Co. We see in a receipt from October 1894 that Thorp & Martin Co. continued the same work as their predecessors, and had a foot in the typewriter world ([Thorp & Martin Co. receipt], 1894).

While Thorp was being sued as a director of Thorp & Martin Mfg. Co., it appears that Tilton Mfg. Co. was moving toward the end of its life. 1893 was the last year that Tilton Mfg. Co. was listed in the Boston Directory (Sampson, Murdock & Co., 1893), perhaps due to the factory fire. We find Fred G. Tilton listed individually with his home in Allston, MA in 1894 (Sampson, Murdock & Co., 1894), and by 1895, we find the 113 Purchase and 50 Hartford St. address associated with Boston Engraving and McIndoe Printing Co.; Fred Tilton was at the same time listed as having “removed to Lowell” (Sampson, Murdock & Co., 1895). As a reminder, the New York office had already been dissolved in 1892, which left only the Philadelphia office. By 1894, 724 Chestnut in Philadelphia was associated with the Victor Typewriter Co. and Frank W. Bailey (Roney, 1894), the man who had helped to form Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co. in the 1880s. But, it was difficult to determine whether these exits meant the company had closed down completely, so I turned to advertisements to see if there were any clues as to the typewriters being sold beyond those dates. It seems that 1892 was the last year of newspaper advertisements for the Franklin and Victor index from 724 Chestnut St., Philadelphia, Tilton Mfg. Co. of Boston, or Tilton Mfg. Co. of 325 Broadway, New York (Typewriters, 1892; Victor Type-Writer, 1892). However, there was one clue that suggested the company remained a legal entity for a bit longer: in 1903, the Tilton Mfg. Co. was excused from making a return in the state of Maine (Public Documents, 1904), meaning they were somehow still considered a live business. This could have meant that the company engaged in so little business that year that they did not make enough to file for taxes. If we add to that the fact that Fred G. Tilton was no longer associated with Tilton Mfg. Co. in the 1894 Boston Directory, and the death of Dr. Thorp in 1895, it seems reasonable to assume that Tilton Mfg. Co. had ceased its main operations sometime around 1893.

The End for Elliott G. Thorp

Sadly, two years after the organization of Thorp & Martin Co., the fire event in the Purchase St. factory, and the likely end for Tilton Mfg. Co., on November 22, 1895, at the young age of 46, Dr. Elliott G. Thorp, the pharmacist turned stationer and inventor, succumbed to Bright’s Disease and died in his home on Waltham St. in West Newton, MA (Elliott, 1895; Obituary, 1895; Cross, 1905; Copy Death Notice, 1895). Just three months earlier, in August, he had been fishing in Maine with Frank W. Bailey, the head of the typewriter department of Thorp & Martin at the time, (Boston, 1895), (and yes, the same man who had helped to form Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co. in the 1880s). Dr. Thorp had continued creating as well. On December 27, 1892, he and Harry E. Gifford had applied for a patent for a Capillary Copying-Bath. U. S. Patent 532,434 was granted on January 8, 1895, and Gifford assigned rights to the patent to Thorp (Thorp & Gifford, 1895). Nothing I found seemed to suggest that anyone was expecting his untimely death. Between the bankruptcy lawsuit, inventions in process, and running multiple businesses, Dr. Thorp must have experienced quite a bit of stress, and Bright’s Disease is sometimes associated with high blood pressure; it is possible the stress was the cause of his decline. He left behind his wife, Harriett, and daughter, Marion. It wasn’t surprising to read that Thorp’s business associates and likely close friends, Fred and Frank Tilton, were pall-bearers at his funeral (Funeral of Thorp, 1895).

Cutter-Tower, Thorp & Martin, and Franklin

As Dr. Thorp's chapter comes to an end, we turn to the typewriters to which his endeavors gave life, the Victor index and the Franklin. Often in these stories we become so entrenched in the lives of the inventors and first vendors of the subject typewriters that we forget to look around at the countless other people and businesses that touch a product. You read about the World index in Part III, which had been transferred between at least three different companies. The Victor index and Franklin typewriters were no different. Although these typewriters were originally assigned to and manufactured by the Tilton Mfg. Co., and although the Franklin Typewriter Co. claimed sales, other companies seemed to have had a hand in their lives as well. The Cutter-Tower Co. was one.

In that fateful year of 1893, the Cutter-Tower Co. was listed as the exclusive supplier of both the Franklin and the Victor typewriters in New England (Correspondence, 1893). The Cutter-Tower Co. had divested its general stationery business in 1891, but kept its patented goods and specialties, which happened to include patents for the Franklin and the Victor index (Mercantile Illustrating Co, 1895). It is hard to tell if they had purchased these patents from Tilton Mfg. Co., or if they were only licensing them. If you remember from Part II, Cutter-Tower Co. was founded in 1845, but was incorporated in Massachusetts in 1878, the same year that Winkley, Thorp, & Dresser had purchased the business of Cambridgeport Diary Co. Cambridgeport Diary Co. had been the successor to Cutter, Tower, & Co., which is very similar in name to Cutter-Tower Co. In 1884, Winkley, Thorp, & Dresser became Winkley, Dresser & Co., and was headquartered in Boston at 12 Milk St. As you read a minute ago, eleven years later, in 1895, we find Thorp & Martin Co. located at that same 12 Milk St. and Cutter-Tower Co. located at 12A Milk St. (Mercantile Illustrating Co., 1895). In other words, Thorp, president of Tilton Mfg. Co., had also owned a business that was located in a building historically inhabited by previously related businesses, and which is the same building as the Cutter-Tower Co., an exclusive supplier of the Victor and Franklin typewriters in New England, which were the bread and butter of Tilton Mfg. Co.

But that’s not all. Before 1895, as you know, the 113 Purchase St. factory of Thorp & Adams, which became Thorp & Martin, was also inhabited by Tilton Mfg. Co. and Franklin Typewriter Co., manufacturers of the Victor index and Franklin typewriters, which were being sold by Cutter-Tower Co. It so happens that at least by 1895, Levi C. Tower of Newton, MA, the President and founder of the Cutter-Tower Co., also happened to be Vice President of the Franklin Typewriter Co. As an aside, one of the directors of Franklin Typewriter Co., William H. Bliss, also happened to be treasurer of Cutter-Tower Co. (Gove v. Tower, 1907). As you can see, Thorp & Martin Co., Franklin Typewriter Co., Cutter-Tower Co., and Tilton Mfg. Co. were all quite inter-connected via personnel, physically through offices and factory, and legally through the Victor index and Franklin typewriter patents and selling rights.

So what became of these businesses? As for the Thorp & Martin Co., after Dr. Thorp passed away, the directors chose to retain his name, and it seems that they were able to turn around their fortune after the string of bankruptcies and failures of their predecessor companies. In 1900, Thorp & Martin Co. was still listed under typewriters in the Boston Directory, and was still located at 12 Milk (Sampson Murdock & Co., 1900; [Thorp & Martin Co. receipt], 1900). By 1905, the company had moved to 66 Franklin (Sampson & Murdock, 1905; [Thorp & Martin Co. trade card], n.d.), and maintained that location, while adding a second location at least by 1918; they located the stationery business at 66 Franklin, and the typewriter supplies, at 70 Franklin (Sampson & Murdock, 1918, p. 300). Advertisements for the store persisted in the newspapers at least through 1952 (Thorp & Martin Co., 1952), and in 1953, the name was changed to Crosby Stationery, Inc. (Schan, 1954).

As you know, the Franklin Typewriter Co. of 812 Greenwich Street in New York didn’t fare quite as well. Going back a little, on June 22, 1899, four years after Dr. Thorp passed on, Robert J. Edwards of Munn & Co. and George H. Hunter loaned a significant sum of money to the Franklin Typewriter Co., which the company was unable to pay back on time. The two men brought a lawsuit against the company in July-November of that year to force repayment of the loan (Gove v. Tower, 1907), but did not succeed. Then, on September 15 of the same year, President George A. Smith and Treasurer E. J. Delehanty of Franklin Typewriter Co. asked for a second loan, a mortgage, this time from that familiar company, Cutter-Tower Co. of 31 Nassau St., New York (Gove v. Tower, 1907; Lawsuit Franklin Cutter-Tower, 1904). A deposit from Franklin was made with David A. Tower, Levi Tower’s nephew (Lawsuit Franklin Cutter-Tower, 1904), but the mortgage wasn’t signed immediately.

On February 3, 1900, Hunter and Edwards brought a new action against the company for repayment, and on October 31, 1901, a verdict was rendered, this time in favor of Edwards (Gove v. Tower, 1907). The verdict was ruled nulla bona, i.e., the creditors could not seize any property from Franklin Typewriter Co. This may have enabled Franklin to pursue a mortgage that could be backed by all of Franklin Typewriter Co.'s property. On December 18, the mortgage was signed with Cutter-Tower; Morton Trust Co. acted as intermediary (Lawsuit Franklin Cutter-Tower, 1904; Gove v. Tower, 1907). Part of the property backing the mortgage included the patents for the Franklin typewriter: Wellington P. Kidder's U. S. Patent 464,504 (Kidder, 1891), George A. Seib's U. S. Patent 590,117, which was assigned to the Franklin Typewriter Co. (Seib, 1897), and George Seib's unassigned U. S. Patent 624,107 (Seib, 1899).

Unfortunately, it seems the mortgage was not sufficient to keep the company solvent. On March 11, 1902, Hunter and Edwards filed a petition of bankruptcy against the Franklin Typewriter Co., and on June 6, 1902, the company was declared to be bankrupt. Franklin Typewriter Co. was unable to pay off its debts between 1902 and 1907 (Gove v. Tower, 1907). Given the potential conflicts of interest between Cutter-Tower and Franklin, one can only imagine the skepticism Robert J. Edwards must have felt about whether he would be treated fairly when it came time to divide the assets of the Franklin Typewriter Co.

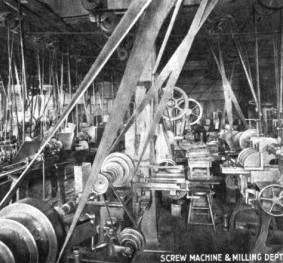

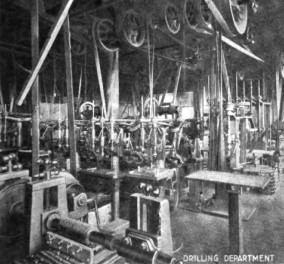

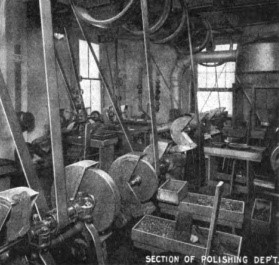

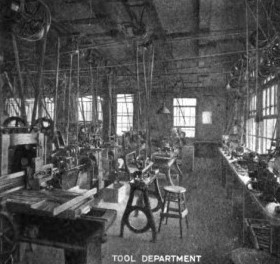

As you may remember from “Rethinking the Franklin”, in 1907, the Franklin manufacturing facility at 812 Greenwich, NY, became the Victor Typewriter Co. and started to sell a standard model typewriter after assuming the assets and responsibilities of the Franklin Typewriter Co. (Best, 1907). Below you can view images of that factory from both the outside and the factory floor. The images were copied from an article on the status of the business, published in the September 1909 volume of Typewriter Topics (Victor Typewriter Factory, 1909). Possibly unrelated, but fun to note, in 1918, there was a Victor Typewriter Service Department located at 12 Pearl, Boston, MA, the same address that was inhabited by the World Typewriter Co. and the Typewriter Improvement Co. in 1900 (Sampson & Murdock, 1918, p. 820).

Life After the Tilton Manufacturing Company

As for the inventor of the Victor index, a few years after the Tilton Mfg. Co. all but shut down, we find Charles Edwin Tilton pursuing an interest in optical mechanics. On June 16, 1898, he specialized in refraction and mechanical optics and graduated from the Klein Optical School of Optics in Boston, MA, at 41 years old (Jacob (a), 1898; U.S. Census Bureau, 1920). He went on to “engage in business” in Boston, MA (Jacob (b), 1898), and for a period continued to make money in jewelry shops as a horologist (U.S. Census Bureau, 1910). Charles and his wife Fannie had a second child, a son, Laurence M., born around 1904 (U.S. Census Bureau, 1910). By 1920, he had found a place in an office working as an optometrist in Boston (U.S. Census Bureau, 1920). Ten years later, Charles and Fannie were living in Boston with their daughter Mildred’s family, including her husband Alfred and their five daughters (U.S. Census Bureau, 1930). Charles passed away in 1937, and was buried in the family plot in Park Cemetery in Tilton, NH, along with his daughter from his first marriage, Winifred, who had passed long ago in 1919, and second wife Fannie, who had passed just four years earlier in 1933 (C. P., 2021; Bob L., 2022).

Three years after Charles had graduated with his optics degree, we find Charles’ oldest brother Frank in mourning. He had been diligently looking after his stationery business in North Adams, MA, when, on November 27, 1901, his wife Rebecca passed away (Mrs. Frank L. Tilton, 1901). She was followed by her husband a year later, who died of Bright’s disease like his good friend Dr. Thorp (Greenfield Items, 1902; Frank L. Tilton Dead, 1902). Although the couple left no children, they had been living with their niece and nephew, who they cared for as if they were their own (Death of Frank, 1902). The store that Frank owned was sold off to settle his estate in the fall of 1904 (Trade Notes (a), 1904, p. 7), and the proceeds likely went to the two children. This sad event left their third brother Fred without any of the business partners who started with him in the stationery business all those years ago.

So what became of Fred G. Tilton, the treasurer and founder of the Tilton Mfg. Co.? In 1900, he was living at a rented home located at 23 So. Walker, Lowell City, MA, with his wife Emma, their 19 year old son Elliott, who was listed as a textile worker like his grandfather before him, and his mother Emily (U.S. Census Bureau, 1900). The Census listed his occupation as stationer, but it seems he was working towards breaking from that life. We find a record that he was a Massachusetts postmaster in 1899 (Dawson, 1899; F. S. Blanchard & Co., 1899), and in December 1903, an announcement was made that “Fred G. Tilton, stationer, Lowell, Mass., is succeeded by H. C. Kittridge.” (Trade Notes (b), 1904, p. 11).

The American Trackless Trolley Company

In June 1902, the same year of Frank’s death, Fred attended a homecoming event in Greenfield, MA (Old Home Celebration, 1902). According to an article written about the event, he, his mother, and his son were all living in different places. This new living arrangement must have freed him for the next chapter of his life. The next year, on March 10, 1903, one-half of a new patent was assigned to Fred G. Tilton of Lowell, MA. This time the patent wasn’t for a typewriter, or in fact anything having to do with the stationery business. It was for a trolley, one that could be operated without the need of a track (Upham, 1903). As Fred was shifting away from the stationery business, he was shifting back towards his youth when he worked on the Union Pacific Railroad. That early experience would have given him a solid base from which he could draw while working on this new mode of transportation. The order winner for this trolley was the cost of installation: the new cars were to cost only $1,600 per mile to install, as opposed to $12,000 per mile for other such systems (Local Short Notes, 1903). In this first decade of the new century, Fred was found listed as the secretary and treasurer of the American Trackless Trolley Co. of Maine, with listings in Boston (Nantasket, 1904; Cross, 1905; Sampson & Murdock, 1905), as one of the the local Pennsylvania agents for the company (Harrisburg Pub. Co., 1905), and as superintendent during construction of the new cars at the factory in Sayre, PA. It seems that Fred was quite literally putting his blood, sweat, and tears into this new endeavor; one day in August 1904, his thumb and forefinger had to be amputated after his left hand was crushed in the machinery (Nantasket, 1904).

In 1905, Fred co-incorporated two new companies with the inventor of the trackless trolley, Artemas B. Upham. With Chas. H. Thurston, they incorporated Thurston Mfg. Co. of MA (Rowe, 1905), and with Chas. P. Sylvester, they incorporated the Nantasket Transit Company of Boston (Moses, 1905). That year, the two men also signed a patent for fireproof stairs (Piccardi, 1905), Fred as witness, and Artemas as attorney. If you have read our other articles, you may have noticed a theme throughout of typewriter businesses around the turn of the century suffering from factory fires. Perhaps Upham and Tilton recognized this danger across the manufacturing industry and wanted to do their part to assist a young inventor with a grand idea that would have been quite useful for the time.

A year later, Fred seems to have expanded his focus to another early theme in his life. On January 26, 1906, Fred Tilton and Artemas Upham co-incorporated the United States Drug Specialty Company of Boston, MA (Rowe, 1906). Perhaps health was on his mind, as sadly, a year later, on April 19, 1907, Fred’s wife succumbed to cancer of the stomach and died at the Lowell General Hospital near their home in Allston, MA (Greenfield, 1907; MA State Vital Records, 1907). Fred stayed with the trackless trolley business, and in July 1908, he co-incorporated the Florida Trackless Trolley Co. of Boston, MA, with Charles Carrison and Frederick H. Sylvester (New Corporations, 1908).

Come 1911, we find both Fred and his son Elliott listed in the Who’s Who of the North Shore of Massachusetts, and the way it is written makes it appear that Elliott may have been in business with his father with the American Trackless Trolley Co. (Salem Press, 1911), but by 1912, Elliott was working for the Western Electric Company in Connecticut (Elliott T. Tilton, 1917), which is where he remained for the rest of his short life. On February 10, 1917, at the young age of 36, Elliott Thorp Tilton passed away. At the time of the article, Fred was living in Fair Oaks, near Sacramento, CA (Elliott T. Tilton, 1917). He must have liked the west coast, or perhaps felt there was nothing left for him in the east, as California is where he stayed. In 1920 we find him living as a boarder in Coronado, CA, and no longer working (U.S. Census Bureau, 1920), and in 1932, Fred George Tilton met his eternal reward. His body was brought back east, and was buried in Park Cemetery, Tilton, NH, sharing a gravestone with his wife and son (C. P., 2021). And it is in Tilton, NH that we end our story of Tilton.

Summary of Discovering Tilton, a Four Part Series

As we started with Tilton, NH, so shall we end with that city, named by a family who wanted to keep their legacy alive. And their sons did just that. In exploring the Tilton brothers and Fred's company, we discovered that typewriters may not have been a main theme in their lives, but were certainly an important part of shaping their histories, the history of a man named Thorp, and the histories of those they interacted with throughout their lives. I hope you have enjoyed this story with its twists and turns and interlocking story lines. It was a story of druggists and railroad men who turned to stationery and the world of typewriters to make a living in the harsh new world of capitalism during the Industrial Revolution in the United States. And it was a story of the Victor index, the World index, and the Franklin typewriter, which had been woven together through the omnipresent name of Tilton.

References

Due to the length of the reference list for this four part series, it has been posted separately. Please see the article titled "Discovering Tilton, References" for a complete list of all sources you will encounter in the text, and from which the pictures were pulled.

Comments